In 1910, Lilian Jennette Rice, a twenty-one-year-old University of California at Berkeley graduate, quietly returned to her family’s home in National City, California — near San Diego — to care for her invalid mother. The homecoming seemed a dreary prospect for the girl who had so recently posed for her University of California yearbook as “the very model of serious young womanhood fulfilling the promise of education and professional status so long denied her sex.” Lilian humbly carried the distinction of being one of the first women to graduate from the School of Architecture. Rather than pursue an architectural career with an established Bay Area firm, she preferred to return to southern California where she had grown up.

The next ten years Lilian devoted to the care of her mother and various positions which included drafting and teaching. In 1921, Lilian’s fateful association with the firm of Richard S. Requa and Herbert L. Jackson provided her with the most unique opportunity of her career. Commissioned by the Santa Fe Land Improvement Company to develop the planned community of Rancho Santa Fe, just north of San Diego, Requa chose to turn this project over to Rice, his associate. As a subsidiary division of the Santa Fe Railroad, the Santa Fe Land Improvement Company purchased land now known as Rancho Santa Fe for the purpose of opening additional orchard acreage to increase freight shipments for the railroad.

Responsible for the over-all plan and supervision of this community, Lilian designed many of the town’s buildings as well as a number of residences throughout Rancho Santa Fe. She knew without being told that this opportunity would give her the chance to show how well she could express her philosophy: the development of a regional architecture strongly allied to the natural landscape and history of southern California.

Lilian’s entrance to Berkeley in 1906 was the realization of a dream fostered by parents who encouraged their daughter to strive beyond the normal range of professions available to women at the turn of the century. As a leading educator in San Diego and National City schools, Lilian’s father, Julius Rice, carefully guided his daughter’s academic growth. Lilian’s education benefitted from her mother’s influence as well. A talented painter with a fine sense of design, Laura Rice gave her daughter an appreciation for aesthetic qualities that balanced her father’s more practical outlook.

By the time Lilian boarded the steamship for Berkeley, her features already reflected the combination of a determined, but romantic, nature. Her pale brown hair, carefully swept up, framed a thoughtful face whose serious expression was softened by a warmth and vitality that characterized her personality throughout life. Of all Lilian’s features, her eyes gave best evidence to her temperament. Their large, downward slant evoked a visionary quality that foreshadowed the dreamer inside. As Lilian began her Freshman year, she little realized how strongly the decades ahead would affect and direct that vision.

Berkeley offered an endless variety of cultural activities for a small-town girl, and Lilian enthusiastically took part in campus life. In addition, the university provided a unique atmosphere for a budding student of architecture. As Lilian walked to class each day, she undoubtedly felt the air of excitement as she watched a whole new campus take shape under the direction of John Galen Howard, head of the School of Architecture. Both Howard and his gifted associates, trained in the Ecole des Beaux-Arts philosophy of architecture, combined their skills to design and supervise the construction of many buildings during Lilian’s years at Berkeley. Howard’s master plan for the university enabled her to witness firsthand the entire design process. The advantages were unmistakable as she saw a unified plan unfold that blended Eastern and European influences with a newer regional style that expressed the desire of the architect to be Californian.

Lilian’s exposure to an original architecture profoundly affected the development of her philosophy. While university architects experimented with new design concepts, their work reflected a greater movement, the influence of which had already spread throughout the Bay Region. The rugged northern California landscape provided the main source of inspiration for this movement. Steep, wooded hills, a moderate climate and the San Francisco Bay provided a majestic setting for “an original architecture uniquely suited to its environment.”

Followers of this movement called for an homogenous blend between building and topography. Their fondness for California’s natural beauty and heritage found expression in domestic architecture that insisted structures harmonize with the land. These architects utilized unfinished surfaces, exposed structural elements and materials indigenous to the environment. They “wanted the colors of both interiors and exteriors to echo the shades of the land,” while “porches and patios extended the house until it met surrounding nature.”1

Building with Nature: Roots of the San Francisco Bay Region Tradition

Although leading proponents of the Bay Area style embodied a regional philosophy distinctive to their locale, none were natives. Prior to their arrival in California, all had worked or traveled on the East Coast and in Europe and had benefited from exposure to the current architectural ideas of the day. Once settled in California, however, they became “immersed in the local past and adopted the local style of living.” In California Design: 1910, Eudora Moore best expressed what a deeply compelling effect the landscape had.

“The one thing which seemed to bind…architect and craftsman alike, which seemed to hover over the entire community in both north and south was a strangely palpable sense of place — of the land and of the individual’s identity with it. There was something new and pervasive about the quality of the western light. The benign climate brought an almost romantic consciousness of nature. There was a sense of timelessness of being in a world apart — a world which could be remade in one’s own vision — in which one’s desired lifestyle could be realized and one’s influence felt.”

When Lilian graduated in May of 1910, she brought this vision home. Following the return to the Rice family home in National City, Lilian divided her energies between an ailing mother and a part-time job in the architectural office of Hazel Waterman. A former Berkeley art student, Waterman had successfully built a reputation as a talented designer through a former association with San Diego architect Irving Gill. She encouraged young women, like Lilian, to develop and pursue professional skills. Later, Lilian taught mechanical drawing and descriptive geometry at San Diego High School and San Diego State Teachers College. About this time she began to work for the architectural firm of Requa and Jackson, an association which had a far-reaching impact on her life.

Through Richard Requa, Lilian again found the ideal of an original architecture. While the wooded Berkeley hills and scenic bay provided the impetus for the development of the Bay Region style, California’s Spanish-Colonial heritage acted as the cohesive element in the formation of a regional architecture to the south. A well-established romantic tradition built around California’s mission days and the vast ranchos that spread across a sun-drenched land, provided a colorful historical backdrop for an architectural idiom that captured the flavor of a by-gone era. Even the landscape seemed to echo the plains and gently rolling hills of Spain. Requa’s extensive travels through that country had reinforced his belief in an architectural ideal based on the Spanish style.

His intention was not to merely reproduce the buildings of Spain, but to adapt in an original manner those features most suitable to the southern California landscape.

In 1922, a commission to design and supervise the construction of a planned development in north San Diego County created a perfect opportunity for Requa and Jackson to build a community based on the California-Spanish style. The distance from San Diego, however, presented difficulties for two busy architects who could ill afford the time to make the many necessary thirty-three mile trips during the project’s construction phase. Also, the prospect of modest financial gains proved a drawback for established professionals who wished to avail themselves of more lucrative offers in town. The decision to turn the project over to their associate, Lilian Rice, not only provided a satisfactory solution to the problem, but offered a distinct challenge for a young woman whose full-time involvement with the firm had occurred only a year earlier.

The first time she drove along the freshly graded roads that criss-cross the hills of Rancho Santa Fe, Lilian was undoubtedly struck by the memory of a young girl who watched the unified plan for a new campus take shape under Howard’s gifted leadership. Suddenly the years of training enhanced by experience with two distinct regional architectures, combined to provide a testing ground for expression of her own ideas. The gently rolling topography, broken only by tall forests of fragrant eucalyptus, provided an ideal setting for the realization of a vision. As Lilian gazed across the landscape, the remnants of old adobes brought to mind the area’s colorful heritage.

Originally, Rancho Santa Fe began as the San Dieguito Land Grant, a 9,000 acre tract of land deeded in the 1830s to Don Juan María Osuna. While descendants of the Osuna family continued to live on the rancho for many years after Don Juan’s death, frequent title changes divided the land into smaller parcels. Despite altered interior property lines, however, the old estate’s exterior boundaries remained intact. In 1906, the Santa Fe Land Improvement Company, a division of the Santa Fe Railroad, purchased the San Dieguito Land Grant and changed the name to Rancho Santa Fe. The land became an experimental site. Several million eucalyptus trees were planted as part of a program to provide suitable wood for railroad ties. When the program failed, the young forests continued to grow unhampered and soon blended with the area’s natural vegetation.

During the 1920s the Santa Fe Railroad’s vice-president, W. E. Hodges, decided to subdivide the ranch into several hundred parcels for orchards and country estates. Concern for the ranch’s great beauty and historic traditions motivated Hodges to use every resource possible to ensure that subdivision preserved the area’s character. The result meant a restricted environment where all new buildings appeared as a “part of the Land Grant’s romantic past. In short, Rancho Santa Fe was designed as a monument to California’s past, as well as an expression of faith in its future.”

As resident architect at Rancho Santa Fe, Lilian found the basis for a planned community well underway. One of her initial contacts included L. G. Sinnard, a man whose vision and sensitivity to the surroundings made him a good choice to direct the engineering aspects of the project. As manager for the Santa Fe Land Improvement Company, he plotted the subdivisions and winding roads that later characterized the ranch’s charm. Sinnard welcomed Lilian as a kindred spirit whose architectural ideals matched his own views regarding beauty and harmony.

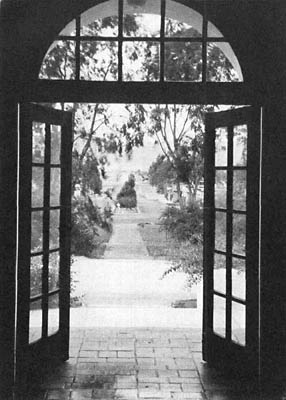

Satisfied with the groundwork laid by Sinnard’s capable staff of engineers, Lilian began to plan the architectural development of Rancho Santa Fe, a task, she later stated, “of tremendous personal interest and satisfaction.” She designed an urban environment that established visual harmony between the community’s buildings and their park-like surroundings. Clusters of residential and commercial structures along a wide, landscaped street, “created a sense of urban space,” while “white-walled townhouses with entrance gates leading to gardens, and arcaded walks created a sophisticated ambiance.” The use of adobe wall construction enhanced the Spanish-Colonial atmosphere and recalled the early days of Rancho San Dieguito.

From 1922 to 1927, development of Rancho Santa Fe occupied most of Lilian’s energies. The Rancho Santa Fe Inn, a school, library and numerous commercial structures and residences all reflected her fondness for the California-Spanish style.

Lilian understood the assessment made by Requa of Mediterranean architecture as a valid form along the coastal regions of southern California. As she worked out the architectural plan for Rancho Santa Fe, Lilian remained true to the concept of a regional style based on the natural beauty and historic associations of the area. Both commercial structures and country residences echoed their surroundings. White or natural-colored adobe walls complemented red-tiled roofs, while intimate patios and courtyards abounded with lush semi-tropical foliage. Stately palms mixed with colorful bougainvillea, banana and pepper trees, recalled the days when mission fathers and wealthy landowners planted gardens as a reminder of their native soil. A fine sense of craftsmanship and attention to detail attested to Lilian’s skills as an architect. Exteriors reflected her desire for a building’s appearance to always “conform to the setting of nature.” In a 1928 architectural journal, Lilian expressed her affinity for the Rancho Santa Fe landscape quite well.

“With the thought early implanted in my mind that true beauty lies in simplicity rather than ornateness, I found real joy at Rancho Santa Fe. Every environment there calls for simplicity and beauty — the gorgeous natural landscapes, the gently broken topography, the nearby mountains. No one with a sense of fitness, it seems to me, could violate these natural factors by creating anything that lacked simplicity in line and form and color.”

Lilian Rice

Simplicity of design characterized all of Lilian’s domestic architecture. The contours of both large estates and small dwellings corresponded to their respective building sites. Preservation of natural features such as rocks and trees created the impression that the structure was but a detail in the landscape. Interiors further enhanced this over-all impression. Open-beamed ceilings, tiled surfaces and varied floor levels added interest without detracting from the visual harmony and smooth flow that united interior floor plan with the outdoor environment.

Lilian’s sensitivity to the surroundings made her realize architectural ideals had validity only in so far as they reflected people’s attitudes toward their environment. The successful development of Rancho Santa Fe reinforced her belief in the necessity for architecturally controlled communities. City planning and protective restrictions were “a natural result of civilization’s progress” and must thwart the careless efforts of those who endangered California’s scenic beauty. “Without control, the heritage of natural charm that nature gave…was further disfigured, instead of being enhanced.” The decision made in 1928 by Rancho Santa Fe homeowners to form an association to ensure the protection of their community, attested to her faith in city planning. Their recognition of the environment and the suitability of an architectural style compatible with the landscape, gave Lilian a tremendous sense of satisfaction and accomplishment. As a key figure in a successful experiment, she envisioned Rancho Santa Fe as a prototype for future developments.

During her career, Lilian’s designs continued to reflect her adherence to a regional ideal. While she worked in a number of communities throughout San Diego County, the heart and spirit of this talented architect remained most visible at Rancho Santa Fe. After an amicable separation from the firm of Requa and Jackson in the late 1920s, she opened her own office and continued to work successfully until her sudden death in 1938.

Lilian’s abilities as an architect were matched only by the warmth and humor that had characterized her entire life. Pleasant working relationships gained this talented woman the respect and admiration of clients and employees alike. Sam Hamill, a former draftsman in Lilian’s office, recalled:

“What I remember most…was the wholesome, sympathetic, and sensitive understanding she brought to student, employee, or client. Her residential designs…seemed to reflect the personality and lifestyle of the client…As a result of this empathy between architect and client, I would venture that the summation of clients paralleled the equal summation of permanent friendships.”

Rancho Santa Fe became the realization of a vision carefully nurtured through years of training and experience. Lilian’s fondness for the California landscape found meaning through a style that not only established a regional identity, but expressed a deep concern for the environment. As an early environmentalist, she sought to create a harmonious blend between building and topography. Combined with her faith in the future role of architecturally controlled communities, Lilian Rice envisioned the time when cooperation between city planner and architect would create communities sensitive to their surroundings and to people’s needs.

1Leslie Mandelson Freudenheim and Elisabeth Sacks Sussman; Building with Nature: Roots of the San Francisco Bay Region Tradition; Kenneth H. Cardwell, Bemard Maybeck: Artisan, Architect, Artist.

This article, first published in the San Diego Historical Society’s quarterly journal in Fall 1983, was submitted by Kelli Hillard who is a Covenant member and serves as president of the RSFA Art Jury.