When the morning sun hits Lake Hodges, it looks less like a lake and more like a warning. What was once 1,200 acres of shimmering blue water, San Diego’s largest natural watershed is now a tinderbox of invasive weeds that stretches from Ramona to Del Mar.

Two years ago, the state ordered Hodges drained to 280 feet above sea level — more than 15 feet below its long-established safe level of 295 feet. The reason wasn’t a failure, but a fear: a hypothetical model predicting an earthquake could damage the 106-year-old dam. The model was never tested against the dam’s actual structure — a multi-arch marvel anchored in blue granite, a design that has never failed anywhere in the world.

Fire Risk 500x Greater Than Dam Failure

What officials didn’t model was the real disaster forming upstream. The exposed lakebed, now over 500 acres of bone-dry grass with moisture levels under five percent, sits squarely in a Cal Fire “Very High Fire Hazard” zone. The Witch Creek and Cocos Fires already proved how Santa Ana winds can turn this corridor into a flamethrower aimed at our homes.

The math is stark: the risk of a catastrophic wildfire like Palisades here is five hundred times greater than the chance of a dam failure.

Meanwhile, 12 billion gallons of local water — enough for 17,000 households — were dumped downstream. Replacing it with desalinated or imported water costs ratepayers up to $120 million more each year. A $208 million hydroelectric and transfer system that once generated renewable power for 26,000 homes now sits idle, its turbines dry.

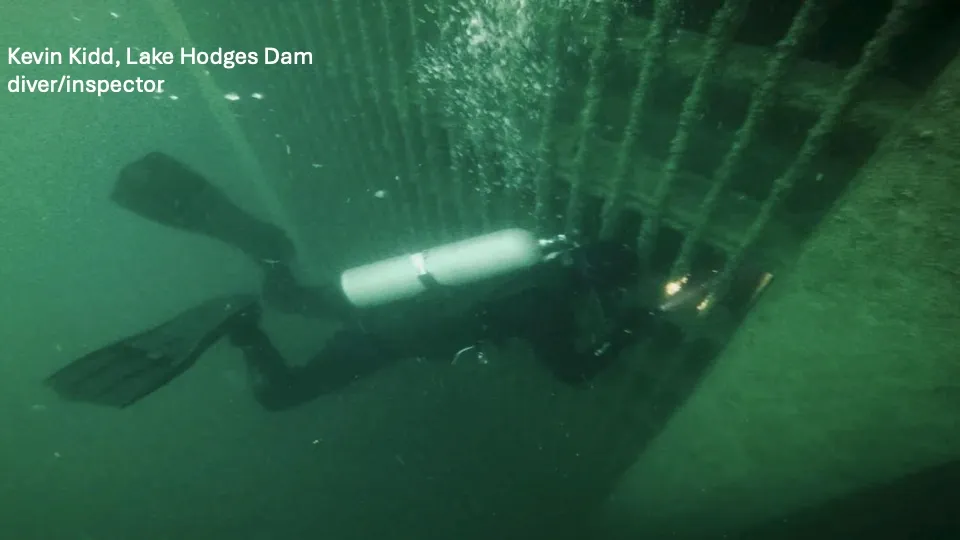

And what’s the payoff for all that loss? None. The state’s own Division of Safety of Dams initially found Hodges structurally sound at 295 feet. Engineers, divers, and emergency specialists who have inspected the dam for decades say the cracks are cosmetic, the structure intact, the foundation unshaken.

Clean Power, Lower Fire Threat, Vital Water Source

Raising the lake a mere 13 feet to 293 — still twenty feet below its full capacity — would drown out those 500 acres of wildfire fuel, cool the valley’s microclimate, replenish a vital water source, and reactivate clean power, all at zero cost to taxpayers. It requires no new concrete, no new permits — just the courage to let nature refill what bureaucracy drained.

This isn’t an abstract policy debate. More than 10,000 homes lie in Hodges’ wildfire corridor, representing $25 billion in property value. Twenty-six endangered species depend on the San Dieguito River Valley wetlands that are now drying into dust. The number of nesting Grebes has gone from hundreds to under ten. Every Santa Ana wind that blows across that exposed lakebed is a lit match waiting for the right spark.

We don’t have to accept this political paralysis where fear masquerades as prudence. Raising Lake Hodges to 293 feet is common sense, not controversy — a move that protects lives, lowers rates, and preserves an ecosystem that has sustained San Diego for a century which is why the Rancho Bernardo Community Council (representing 45,000 residents), Del Dios Town Council, San Dieguito Planning Group, Rancho Santa Fe Association, Citizens Advisory Committee for the San Dieguito River Park, Friends of San Diego’s Lakes, and the Sierra Club all support this.

History will judge whether we learned from past fires — or merely waited and did nothing to prevent the next one.

Visit RaiseLakeHodges.org to read the science, see the data, and join the growing coalition urging our state and local leaders to act — before the lake that once protected us becomes the spark that destroys us.

Dr. Bernstein is a member of the San Dieguito River Park’s Advisory Committee and is a longtime North County resident.